Prof. Thomas Farrell: 'Reflective Practice for language teachers'

IH Teacher Training, Barcelona. Teacher Development Seminar, 5th June, 2018

Prof. Thomas Farrell: Reflective Practice for Language Teachers

Introduction

Prof. Thomas Farrell (Brock University, Canada) was invited by the Teacher Training Dept. at IH, Barcelona to give a seminar on Reflection in Language Teaching for local EFL teachers. The session started with an invitation to reflect (!) on what Reflective Practice (RP) actually is. It is universally understood to be a mark of professional practice and pre-service teachers are often asked to keep a Reflective Journal as part of their teaching practice. However, experienced teacher educators are aware that many trainees simply ‘fake it’ and complete their journals with what they think their trainers want to hear. |

| Defining Reflective Practice |

Identifying Classroom Issues

In order to illustrate how RP might work, Prof. Farrell used a classroom problem that most language teaching professionals will be familiar with:What do you do in this situation? We were invited to compare ideas with a partner, but, as Prof. Farrell warned, there is no one ‘answer’ to this problem. RP offers a number of ways of approaching the problem, which may lead to a solution for your unique situation and unique group of learners. These are based on insights from the work of John Dewey (1859-1952) one of the major advocates of educational reform in the 20th century.

Insights from Dewey

|

| John Dewey |

Dewey suggested slowing down the interval between Thought and Action. As teachers, under pressure from our institutions or the syllabus, we are often guilty of cramming content into the last 10 minutes of class in order to finish the unit. The Slow Teaching Movement advocates using the last part of class as an opportunity for learners and teachers to reflect on the lesson, based on the five principles of Reflective Inquiry:

1. Suggestion

2. Intellectualization

3. Guiding Idea

4. Reasoning

5. Hypothesis Testing

1. Suggestion: Identify the issue. In this case – the students won’t / don’t speak in class. A number of ideas spring to mind which might explain this situation. As we are confident in our teaching abilities, we may be tempted to assume that the problem lies with the students. However, it is important to suspend immediate judgments, the problem could be related, for example, to the currículum.

2. Intellectualize: The next step is moving from an emotional reaction to an intellectual reaction, or in other words from an issue felt to an issue to be investigated. The issue can be refined by asking probing questions. As Prof. Farrell observed

A question well asked is half the answer

This may involve (reluctantly!) asking yourself whether the root of the issue resides in your teaching practice.

3. Guiding Idea: This involves exploring ALL possibilities and reviewing the problem from different perspectives, or through a different lens, as summarised in the following slide:

|

| Guiding idea |

- The Teacher Lens: What do I do now?. It is important to be aware that this is not what you think you do, but what you actually do. At this point, Prof. Farrell advised against telling a teacher what to do, as this will lead to a condition known as ‘learned helplessness’ (Seligman, 1972), when people feel helpless to avoid negative situations.

- The Colleague Lens: Allow a ‘critical friend’ (a trusted colleague) to observe and analyse the problem. It is important to emphasise that ‘critical’ in this sense does not mean looking for the negative, but rather holding up a mirror to your practice. Teachers already have a tendency to be very self-critical, this will only be exacerbated by criticism from others. Prof. Farrell even compared an evaluative observation done by a supervisor as a ‘drive-by shooting’!

- The Student Lens: What do students think I do? Students are observing us in every class and are ultimately our target clients/customers.

- The Literature Lens: What do others do? While Prof. Farrell made the point that many teachers run for the door at the mere mention of research, it is possible to find examples of research written by teachers for teachers which can usefully inform your practice.

Practical example: Reviewing an EAP lesson through the Teacher+Colleague+Literature Lens

Prof. Farrell was asked to observe an EAP lesson which involved a 30-min. student presentation, followed by 10 minutes Q & A. The teacher was experiencing the ‘students don’t / won’t speak’ problem mentioned before and had asked him to help her reflect on her practice. A SCORE analysis was used to map the interaction throughout the class (see slide below)

|

| SCORE analysis |

This is a low inference analysis – the observer maps the position of the people in the room and notes down when, how long and between whom each interaction occurs. The analysis revealed that the teacher asked 45 questions and the wait time in each case was less than one second. The teacher was completely unaware that she was doing this.

The addition of the ‘Literature Lens’: exposes the teacher to relevant research on the topic, allowing her to see how extending the wait time can lead to increased number and length of student responses.

|

| Literature Review Lens |

4. Reasoning: Based on the evidence gathered, the teacher makes a tentative plan to reconsider her approach to questioning:

|

| Reasoning |

5. Hypothesis Testing: As a teacher, you can try out your ideas, but don’t worry if they don’t have the desired effect. In the EAP class, the teacher made a conscious effort to increase the wait time to 3 seconds (by pinching herself!), which had a corresponding effect on the amount and length of student responses (see following slide):

|

| Second SCORE analysis |

Dewey’s proposal of reflective enquiry, a precursor of Action Research, encourages the teacher to collect evidence (Prof. Farrell deliberately chose not to use the word ‘data’) about their practice which will allow them to make informed decisions:

|

| Evidence-based Reflective Practice |

Types of reflection

At this stage, Prof. Farrell pointed out that Reflective Enquiry is just one possible type of reflection (Reflection – ON – action). He introduced three different types, summarised on the following slide, and then elaborated on each one in turn: |

| Types of Reflection |

Reflection – IN – action: An experienced teacher has a hawk’s eye view of the class and can read and interpret development and interaction as it happens. This is ‘on-the-spot’ reflection where the classroom is the centre of enquiry.

|

| Reflection 'IN' action |

Such online decisions may be made on the basis of questions such as: ‘Are my instructions clear?' 'Am I including everybody?’. For example, in an observation study conducted by Prof. Farrell into the ‘Teachers Action Zone’ (the area in which the teacher moves and interacts), 138 out of 140 teachers ignored the left-hand side of the room without being aware of it!

Other questions to consider in the moment may include: ‘Are my activities going as planned?’ ‘Are they too easy / too difficult?’. One area ripe for relection, as we have seen previously, is teacher questions: ‘How many?’ ‘What type: display or referential?’ ‘Do I leave enough wait time?’ etc. Below is just one extract from a transcription of a situation which teachers will find painfully familiar: a sequence of teacher questions met with silence from the group, until finally one student raises her hand.

|

| Transcript of classroom interaction |

Michelle’s answer was: ‘Can we give in the grammar homework on Monday’?

This is a class which did not go to plan. The teacher and students were working from different frames of reference. The teacher assumes that the learners are all following, while the learners are preoccupied because they haven’t understood the homework. There is simply no one-to-one correspondence between what the teacher teaches and what the students learn. At this point, Prof. Farrell reflected that Dewey would say

‘Teach the students first, then teach the book or material’

Reflection – ON – action: After the class, we ask ourselves ‘What happened?’ ‘What did the students learn and how do we know?’ Prof. Farrell suggested that this is where we should bring in our learners’ voices. They should also be asking ‘What did I learn today?’.

|

| Reflection 'ON' action |

The traditional way of finding out what and whether our students have learnt is by testing, either formally or simply asking ‘round up’ questions in the last 10 minutes of class, e.g. ‘What’s the past tense of GO?’ (usually directed at the best student!).

|

| Reflective learning |

Alternatively, we can use these last ten minutes to offer our learners the opportunity to reflect (returning to the ‘Student Lens’ mentioned earlier’). At the end of the class, ask the students:

- What was the class about?

- What did you learn?

- What was difficult?

Students are not used to this type of reflection, and may struggle to answer at first. A teacher in S. Korea posed the questions at the end of a class and got the following answers:

|

| Initial student responses |

She repeated the activity in the following class and got exactly the same answers. It wasn’t until the third attempt, when she asked her students to focus on their own experience as learners, that answers began to emerge that were relevant to her teaching e.g. about her pronunciation (although how she intended to ‘change’ her pronunciation was not made explícit)

|

| Student responses after prompting |

Reflection – FOR – action: Before the class, ask yourself ‘What will I do?’. This is the proactive planning stage, which can combine the results of the –IN- and -ON- refective stages. This may involve reflecting on such issues as:

- What do I want my students to learn from this lesson?

- What are my students’ fears?

|

| Reflection 'FOR' action |

Prof. Farrell pointed out that experienced teachers will abandon a lesson plan if they see that it is not working. In contrast, a novice teacher will stick to the lesson plan, no matter what!

In another example of an observation study, a teacher wanted to ensure that she distributed questions fairly, asking at least two questions to each student. A SCORE analysis revealed that three learners in the group received 70% of the teacher’s attention, much to her surprise.

|

| Three students dominate the classroom interaction |

The participants were invited to discuss what they would do if faced with this situation. Once again, there is no one right answer. The teacher in this case consulted a group of her fellow trainees, who suggested the ‘Speaking Sticks’ technique. Each student in the group is given two speaking sticks, each stick represents an opportunity to speak (Prof. Farrell suggested ‘borrowing’ some of the stirring sticks from Starbucks).

|

| Give me the talking stick! |

As teachers, we may tend to favour the more active, voluble students, when it’s perhaps the quieter ones that need our help most. This teacher’s conclusion was:

‘My shy students realized that I care about them as well. And even if I cared before, now I can really show them that!’

Reflective Practice: Some considerations

CAUTION: Reflection is dangerous! It can actively change your routines:- You have to undergo the trouble of searching (for answers)

- You need to endure the suspense (no clear answers)

Reflection brings with it an inherent duality:

- It is a cognitive act

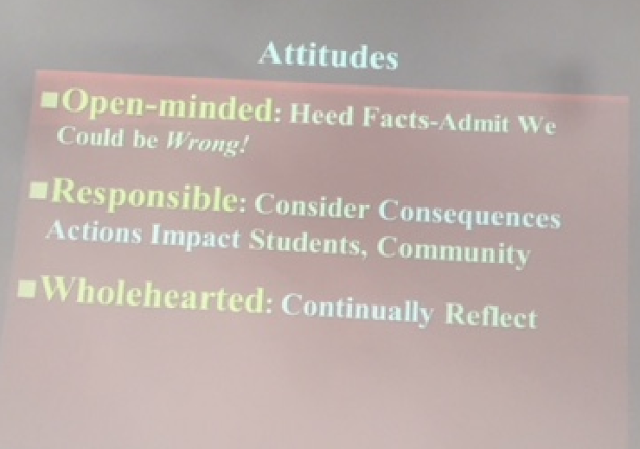

- Accompanied by a set of attitudes (see below)

|

| Reflective Practitioner: Attitudes |

1. Open-minded: Can you keep an open-mind even if faced with the possibility that you may be in the wrong? Here is an example of learner feedback from early in Prof. Farrell’s career in Ireland:

|

| Learner feedback: Harsh but fair? |

2. Responsible: Consider the moral aspect of what we do, and the impact it has. For example:

|

| Levels of responsibility |

|

| Reflective cycle |

Conclusion: The benefits of Reflective Practice

- A teacher should be continually striving to improve and therefore should feel that tension between beliefs and practices.- A reflective practitioner should be able to elaborate their own teories based on practice.

- RP can help teacher develop resourcefulness and resilence.

|

| What can Reflective Practice do for you? |

References

Dewey, J. (1897) My Pedagogic Creed. Facsimile Publisher (2015)Dewey, J. (1909) Moral Principles in Education, The Riverside Press Cambridge, Project Gutenberg.

Seligman, M. E. P. (1972). "Learned helplessness". Annual Review of Medicine. 23 (1).

Comments

Post a Comment